Dogs bite for lots of reasons. They can bite in aggression, of course, if they are defending a resource or guarding their territory. They can also bite in play, usually showing what we would call an inhibited bite. Dogs bite to catch things and to stop prey moving – a habit most of us would prefer our dogs didn’t have. Dogs bite because we’ve bred them to. Cocker spaniels grab birds and labradors grab ducks and bull breeds grab bulls. Dogs bite when it’s useful in herding to move recalcitrant cattle along. Dogs bite to stop a fleeing criminal because we’ve taught them to and they bite because they haven’t learned not to. Dogs bite to eat, of course. They bite to snap at flies and they bite to groom. They grab their babies to move them and they grab their babies to stop them moving too. They can also bite because they’re irritated or because they’re being annoyed. They can also bite because they’re frustrated. They can bite because they want to bite something else but they can’t get to it. They bite by accident and they bite on purpose.

So when I get a call to say a dog has bitten, it’s not as cut and dry as it might seem. I need to know what the circumstances are, what the motivation is, what the function of the behaviour is and what the emotions are behind the bite. The context is vital.

More people call me with one type of bite than most others. A man called me to say his great Dane had bitten him on the leg. They were just playing and boom, his dog bit him on the leg. The very next day, a lady called me to say her labrador had bitten her on the arm when they were out on a walk. I got well and truly ‘Nesquicked’ by a young spaniel at the shelter (whose name was Nesquick of course). The last call was very similar: the lady was out on a walk and her dog jumped up and grabbed her arm. Anyone who’d walked one dog we had in the shelter was immediately evident by their ripped t-shirts, always ripped in exactly the same place under the armpit. No real damage but frightening nonetheless.

The context for these situations may not seem very similar, but it’s usually at a moment of excitement and stress for a dog. Whether that’s a walk or in play, at a social event or in the park, or even waiting to go out for a walk when you’re a kennel resident, excitement and overarousal are common denominators.

Most aggression is what we call ‘distance increasing behaviour’. The purpose of an aggressive bite is to make you cease and desist. But these bites weren’t like that. They weren’t accompanied by growls or snarls, snaps or hard bodies and hard eyes. In fact, they were usually accompanied by a whole set of other behaviours that nobody would ever confuse with aggression. That’s not to say they are ‘warning bites’ or that they are controlled though. Some of the worst bites I’ve seen haven’t been because the dog was aggressive – and we’re talking stitches in the hundreds from some of these non-aggressive bites.

The emotion isn’t the same with some of these bites either. It’s not fear or anger, no sense of threat or challenge. The dogs aren’t in a panic state. There’s no sense of fight or flight. Sometimes the underlying emotion is frustration – that something isn’t happening quickly enough. Other times I want to say the dogs are just plain over-aroused.

Worse still, they may not even seem to be over-aroused at that very moment.

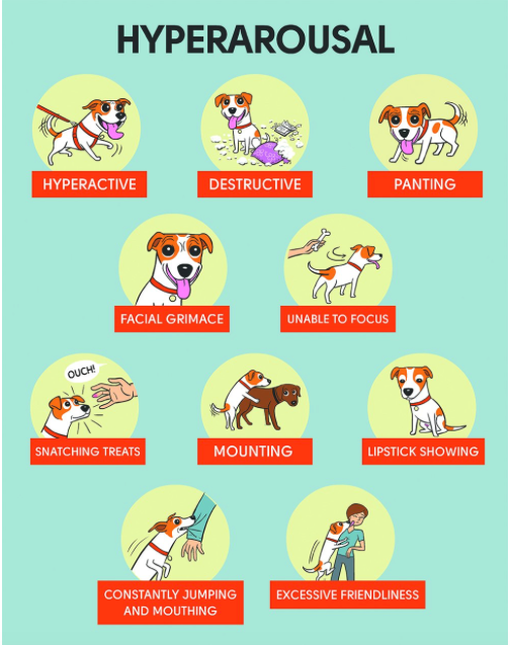

Let’s look at the key markers of over-arousal:

Every single one of those dogs had three or four of these, if not more. And that brings me back to the function or the motivation. I think in these cases, the function was actually to engage the human being in some way. Bizarre, I know. But many of these dogs will be the humpers, the jumpers and the dogs who can’t seem to give you attention for more than a millisecond.

Most of these dogs shared something else in common as well. Many were big, male dogs who’d not had as much socialisation with humans as they should have before 8 weeks or so. They rarely went out with other dogs if they lived in a home, and they would often be a bit of an embarrassment at doggie meetings. For the dogs in a home, they all lived on their own with adults who hadn’t really kept up their doggie meet-ups (mainly because the dog was a bit OTT) and even though all the dogs were very, very loved, they had limited lives and felt a bit ambivalent about their families. Kind of “I love you, but you make me anxious”.

This often happens with castrated teenage males whose owners were cautious about exercising them too much. It equally happens though with dogs who just don’t seem to have an off-switch, and I find families saying, “but we walk him three times a day!”.

The problem is that they’re building super-athletes who’ve got immense stamina, and still can’t manage their own emotions.

The first steps are largely preventative when the dogs are puppies: if you know they are going to grow into big dogs, make sure you teach them a settle. Teach them how to do nothing. Teach them to wait. Some dog trainers call this impulse control. Others call it having good manners. Some think it is to do with taught calmness. Others think it is frustration arising from understanding the cues in a situation that say ‘it’s walkies’ or ‘it’s playtime’ and not having that immediately happen. Either way, the best way to ensure you don’t end up with a teenage ne’er-do-well is to teach them what to do between a signal that something exciting will happen (like food bowls arriving, car doors opening, games starting or leads coming out) and the arrival of that event. Knowing that something good will happen and having time before it’ll be delivered is fertile breeding time for both frustration and anger. Zen bowl, taught waits, clear ‘ready?’ and ‘over!’ cues are some ways you can do these. Personally I think these are exciting moments and if you are constantly asking your dog to sit, to lie down, to go to their bed, you’re just punishing your dog for being happy, so these behaviours are likely to fail. I like something active that gives the dog something to do, but that’s just me. If you want them to sit by the door whilst you get the lead, then that’s your prerogative. Know, though, that if you took me to Disneyland and then asked me to wait at the gate, I’m going to get frustrated eventually.

So some of the time, it’s just about managing the environment. You know when you’re about to do something exciting involving your dog. Your dog knows too. Give them something to do whilst you prepare and you won’t find as much frustration. Yes, Heston and I still have 5 or 6 games of Fetch! whilst I’m putting my boots on for a walk, but he’s not barking in my face or spinning like a dervish. That works for biting too. Stop asking for calm if you haven’t taught your dog to be calm. By teaching them to be calm I don’t mean telling them to be calm and hoping they’ll do it. I mean a proper, planned programme with a good dog trainer or book (Steve Mann’s book Easy Peasy Puppy Squeezy is a great start, and Jane Killion’s Puppy Culture website is brilliant). But instead of thinking that your dog can’t control themselves, start thinking about how you can make it easier for them not to have to.

Also, build up your dog’s mental enrichment. This comes in many forms and you’ve got to remember all of your dog’s basic needs. Some of those might be touch-related with Ttouch or canine massage. They may be social needs, such as the need to be with people, or as is so often the case with over-arousal in the family home, to have contact with other dogs. That doesn’t mean throwing them in a dog park and hoping for the best. It means finding a dog buddy who has similar energy levels and play styles. Taking your GSD to chase hundreds of running poodles is not enrichment. Dogs do teach each other, and some of the best learning has come from a ‘Momma Pack’ of well-socialised, playful adult females who can teach your youngster how to play properly. Think carefully about which dogs will work best and use a behaviourist to facilitate if necessary. It can easily erupt into a dog fight if your dog has got very few playskills. Equally though, if your dog is the equivalent of a preschooler on haribo, you don’t want to take him to play with another preschooler on Sunny Delight and coke.

Mental enrichment can be social, but it can also tie into your dog’s breed and behavioural needs. Got a mental spaniel? Do some gundog work with him. Got a shepherd? Let’s get him working in partnership with you through rally or heelwork. Got a terrier? Let’s get a digging pit and some bones to dissect. And just because you may have a pedigree dog doesn’t mean they don’t have needs beyond the breed. Cockers like chewing too.

Chewing and licking can release all kinds of good hormones and neurotransmitters – chewing tells the body to switch off and go into rest-and-digest mode. That lowers stress hormone production and increases serotonin, the well-being chemical. Licking releases endorphins too. Lickimats and stuffed Kongs are just a starting point. Whilst I’m on the subject of food, you may want to check you aren’t feeding them a diet that’s contributing to it: some supermarket ranges aren’t as trustworthy about quality and chemicals as they should be. That doesn’t need you need to ditch everything you’ve been doing and go to ethically-sourced locally-produced hand-reared ostrich fillets, but at the same time it’s worthwhile knowing that food can make a difference. Check with your vet though. You can always carry out a bit of an experiment and switch for a couple of weeks then switch back to see what happens.

Another of the feelgood chemicals is dopamine – the chemical behind our seeking, chasing and hunting behaviours. It’s what drives our interest in things, what makes us curious. Scentwork, nose games, trailwork, mantrailing and even things like snuffle mats or Sprinkles™ can help with that as they engage your dog’s curiosity and finding skills.

Whilst you will have been tempted to do more physical exercise with dogs who are over-aroused, it’s counterproductive and can turn them into superathletes in need of an adrenaline fix. Believe it or not, a week or so’s break from walks and over-stimulating situations can really help. Make sure, too, that they get lots of sleep. Young dogs need up to 18 hours of sleep. 14 is a minimum. That should be relatively undisturbed. You don’t need a crate or a dark room, but know that if you expect your dog who needs twice as much sleep as you do to be with you everywhere, then they’re not getting as much rest as they should do. You’d think that would end with exhaustion, but just like people who are manic, lack of sleep fuels the mania and lowers all rational thinking.

And although I am not a fan of ‘learn to earn’ programmes, or Nothing In Life is Free kind of things, going back to a basic obedience programme can help to re-establish those ‘I’m the adult here’ boundaries.

So bring down the amount of physical exercise, increase the mental exercise you are doing with your dog and re-establish your basic obedience routines and you should find that your dog’s teenage moments are soon a thing of the past.